Like what you’re reading on the Maison de Traduction? Please support our work by making a donation via PayPal. You can designate your PayPal donation in $ or Euros to paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Or write us at that address to find out how to donate by check. For context to the excerpt below, we suggest reading our excerpt from the Prologue first. The subtitle for this chapter is “(1899 -1917)”; the segment is set in 1911.

Original text by Michel Ragon, copyright Albin-Michel, Paris

Translation by Paul Ben-Itzak: (Abbreviated version originale follows)

“As for me, I’m just a poor sap! For those of us at the bottom of the heap, it’s nothing but bad breaks in this world and the one beyond. And of course, when we get to Heaven, it’ll be up to us to make sure the thunder-claps work.”

— Georg Büchner, “Woyzeck,” cited on the frontispiece of Part One of “The Book of the Vanquished.”

“Sometimes it’s better to be the vanquished than the victor.”

–Vincent Van Gogh, cited in Lou Brudner’s preface to “Büchner, Complete Works,” published by Le Club Français du livre, Paris, 1955.

Translator’s note: With the exception of Fred and Flora, who may be real, may be fictional, or may be composites, all the personages cited below are based on real historical figures, notably Paul Delesalle (1870-1948), the Left Bank bookseller. Later adopting the pen name Victor Serge, Victor Kibaltchich (1890-1947) would become a noted Socialist theorist who, like Fred later in “The Book of the Vanquished,” eventually broke with the Bolsheviks. Raymond-la-Science, René Valet, and Octave Garnier were real members of the Bonnot Gang, the details of their denouement recounted by Ragon as translated below accurate. For the other personalities evoked, including leading figures in France’s Anarcho-Syndicaliste milieu in its heyday, as well as certain events alluded to, I’ve included brief footnotes at the end, as these personalities and events may not be as familiar to an Anglophone audience as to Ragon’s French readers, for whom they represent markers in the national memory, notably the “Bande à Bonnot.”

Every morning the cold awoke the boy at dawn. Long before the street-lanterns dimmed, in the pale gray light he shook off the dust and grime of his hovel at the end of a narrow alley hugging the Saint-Eustache church.(1) Stretching out his limbs like a cat he flicked off the fleas and, like a famished feline, took off in search of nourishment, following the aromas wafting down the street. With Les Halles wholesale market coming to life at the same time, it wouldn’t take long for him to score something hot. The poultry merchants never opened their stalls before they’d debated over a bowl of bouillon, and the boy always received his portion. Then he’d skip off, hop-scotching between trailers loaded with heaps of victuals.

Every Friday he’d march up the rue des Petits-Carreaux to meet the fishmongers’ wagons arriving from Dieppe, drawn by the odor of seaweed and fish-scales surging towards the center of Paris. The sea — this sea which he’d never seen and which in his imagination had assumed the proportions of a catastrophic inundation — cut a swathe through the countryside before it descended from the heights of Montmartre. He could hear the carts approaching from far away, like the rolling of thunder-bolts. The churning of the metallic wagon wheels stirred up a racket fit to raise the dead, amplified by the clippety-clop of the horseshoes. Numbed by the long voyage, enveloped in their thick overcoats, the fishmongers dozed in their wagons, machinally hanging onto the reigns. After all, the horses knew the way by heart. When the first carriages hit the iron pavilions of the market, the resultant traffic jam and grating of brakes rose up in a grinding, piercing crescendo that reverberated all the way back up to the outskirts of the Poissonnière (2) quartier. The drivers abruptly started awake, spat out a string of invectives, and righted themselves in their seats. Those farther back had to wait until the first arrivals unloaded their merchandise. The horses pawed the ground and stamped their feet. The majority of the men jumped off their carts to go have a little nip in the bistros just raising their shutters.

On this particular Friday, at the rear of one of the chariots sat a small girl. Her naked legs and bare feet dangled off the edge of the cart, and the boy, fascinated by this patch of white flesh, approached the wagon. The girl, her head drooping, her face hidden by a cascade of blonde curls which fell over her eyes, didn’t notice him at first. As for the boy, he only had eyes for those plump gams poised on the precipice of the chariot. By the time he was almost on top of them, he could hear the girl singing out a rhymed ditty. He advanced his hand, touching one of her calves.

“Eh! Lower the mitts! Why, the nerve!”

At this point the boy got his first glimpse of her face, a drawn visage with blue eyes. He knew that the sea was blue. The small girl came from the sea. Now that he thought of it, she reeked of fish, unless the odor was coming from the cart. Strictly for purposes of verification, he held his nose up against one of the white legs and sniffed.

She put up a fight.

“Would you mind not snorting like that? In the first place, where did you come from?”

He pointed down the street with a vague air.

“We’re here!” responded the girl. “It’s about time.”

She jumped off the wagon. The boy towered over her.

“I’m 12 years old,” he declared. “And you?”

“Eleven.”

“You sure are tiny.”

“You’re the one who’s tall. What a bean-stalk! You’re as skinny as a kipper.”

The line of wagons had ground to a halt. The men and women had emerged from this tide and floated down to the bistros, from which emanated the hubbub of their boisterous kibitzing. The girl verified that everyone had already abandoned her cart, returned to the boy still planted in front of the wagon gawking at her, took his hand and hauled him off in a trot.

“I’ve had it with these hicks,” she declared when they finally paused to catch their breath, near the rue de Richelieu. “We’re going to make a life together. What’s your moniker?”

“Fred.”

“Mine’s Flora. You crash with your ma and pa?”

“Nope. I manage to get by on the streets. My old man and mom are dead and buried.”

“You’re lucky. Mine are going to come looking for me if you’re not clever enough to hide me. They work me like an ox, and I’ve had it up to here. Watch out — they’re dangerous. If they ever find out that you kidnapped me, they’ll carve you up into little pieces!”

“But I never kidnapped you!”

“You sniffed my legs.”

“I just wanted to find out if you smelled like fish.”

“That’s how it always starts. Then before you know it, you’re hitched.”

They turned off into the gardens of the Palais Royal. Flora’s eyes grew bigger at the sight of the water shooting up out of the fountains.

“What’s the sea like?” asked Fred.

“Disgusting. It never stops budging. It’s full of salt and all kinds of icky stuff. It’s freezing cold, it’s viscous — it sinks the boats of poor fishermen. Sometimes it opens up its huge mouth and bites all the way up to the shore, as if it’s going to swallow up the houses along the docks. It hammers, it howls. I hope I never see its stinking hide again.”

“Here too,” Fred noted, “sometimes the sea rises up from all sides and then it spreads out. Last year Paris just about drowned — and all the Parigots with it. The sea came from far away, seeped into the basements, and then overflowed. Rats scurried down the streets like madmen, the water nipping at their butts. Entire blocks just disappeared, replaced by rivers. Bridges were erected made of planks of wood. Sometimes it sounded just like canon-fire — the ground-floor windows exploding. The water poured into houses and pushed up the sewer grills. Paris smelled like mud, cemeteries, fog. All the lower neighborhoods were wiped out. Only then did the flood thin out, leaving behind it just the sound of the waves — as if the water was quite satisfied with itself for the mess it had made. This is how I think of the sea. I used to hear stories about entire drowned villages sunk to the bottom of the ocean where the church bells still rang out.”

“It’s not like that at all! I already told you, the sea is like one huge garbage dump.”

They were sitting in iron chairs at the rim of the grand fountain, with Flora once again swinging her naked legs from her short, worn, chestnut-colored cotton skirt.

“There’s no doubt about it,” Fred declared. “It’s not humanly possible how much you smell like fish. Are you sure cats don’t follow you down the street?”

Flora shrugged her slight shoulders and bit her nails.

Just then a uniformed guard seemed to spring up from nowhere, huffing and puffing like a bulldog. They barely had time to jump out of their chairs to avoid being clobbered.

“Scram, you little rapscallions! Vermin!”

The pair skedaddled towards the Comédie-Française, hand in hand. When they got to the rue de Rivoli, their ragged clothing jarred with the chic surroundings. Fred, coiffed with a cap, wore an old grey suit. These together with his oversized combat boots leant him the air of a wandering apprentice. Unusually tall and looking older than his age, he might have passed unnoticed in the hoity-toity neighborhoods. But Flora, with her skirt just a little too high, her naked legs, and above all her bare feet, resembled one of “The Two Orphans.”(3) So much so that a well-to-do lady took pity on her and handed her some money.

“What did she give you?”

Flora opened the hollow of her hand to reveal the shining coin.

“Formidable! Let’s treat ourselves to some breakfast rolls.”

Ever since the Great Paris Flood of 1910, Fred had been living on the streets. His father, a manual laborer in the Metro tunnels, succumbed to tuberculosis shortly before the flood and his mother followed suite not long afterwards, swept away by the epidemic. The child was taken in by relatives who weren’t crazy about the idea. Fred took advantage of the general bedlam that followed the surging tides to decamp. What with his adoptive parents assuming that he would “depart this Earth via his chest” anyway and that “what he needs most is fresh air,” he’d not had a roof over his head since running away. In the Les Halles quartier, vagabonds of his stripe abounded. Of all ages. Of all types. From the run-of-the-mill hobo to the Bohemian artist, from the lowest of whores to the Madwoman of Chaillot. Around the iron Baltard pavilions which housed the market swarmed a nocturnal fauna which nourished itself on the refuse of the great wholesale market. Each citizen appropriated himself his own zone, sleeping in his own particular corner. Each vigorously defended his territory. But he who scrupulously heeded the tacit rules of hobo-dom had nothing to worry about. In this veritable cesspool, the boy acquired all the tools of survival. He learned how to sleep with one eye open, his mind alert, ready for anything. He learned how to get by on very little, to subsist on availing himself of water only when the opportunity presented itself. He learned how to duck and dodge blows, to be suspicious and wily. All tools which in later life would enable him to circumvent many a roadblock and pitfall.

All day long Fred and Flora entertained themselves galloping about the streets of Paris. By the time night arrived, Fred was ready to quit. Flora obviously refused to return to Les Halles, where they might be recognized. Yet outside of his quartier, Fred felt lost. He had the impression that since dawn he’d discovered some wondrous places, but he’d never for a single instant considered the idea that when night fell he might not be able to return to his niche near Saint-Eustache. At the same time, abandoning Flora was out of the question. This dilemma lead them to continue skirting the city center until they’d wound all the way up to the working-class neighborhoods of Eastern Paris, where they were startled to find themselves suddenly in the midst of a sort of countryside, with cottages surrounded by gardens, hangers, and craftsmen’s ateliers. Night came upon them all at once in this setting, which felt ominous. They were famished. Fred didn’t want to admit it, but he was lost.

“So, young lovers, just idling about?”

Fred and Flora got ready to bolt when this voice spoke to them from out of the shadows. But once they’d made out the silhouette of their interlocutor, they were re-assured. It belonged to a very young woman, no more than 16, dressed in a black schoolgirl’s smock. Her short hair, parted in the middle, the white sailor’s collar which highlighted her blouse, and her mischievous, charming little face immediately inspired the confidence of the two children.

“I’ve not seen you two around here before. Where are you staying?”

Then, as the children seemed to be tongue-tied, by way of excuse she added:

“You probably think I’m butting into something that’s none of my business. And you’re right. I was just trying to shoot the breeze — my way of saying ‘hello’! Anyways, good night.”

“Wait, don’t leave!” Fred implored her. “I think we’re lost. Are we in the country, or what?”

“You are in Belleville. A not very beautiful ville. (4) Belleville is the boonies. And that’s exactly what we love about it. But I’m a dolt — perhaps you’re hungry?”

“Yes,” answered Flora.

“In that case, come along.”

The young woman opened up an iron gate, lead them through a garden, and they mounted, via a wooden stairway, to a modest lodging where a young man stood at a table carefully reading large sheets of newsprint. He also seemed very young, 20 at most. He was dressed in a peculiar white flannel shirt with mauve silk fringes. His black eyes studied the two children.

“This is Victor,” said the young woman. “I’m Rirette.”

“I’m Fred, and this is Flora.”

“Well, Fred, well, Flora, you’ll have some bread and a little cheese. Victor and I won’t ask you any questions. If you have no place to sleep, there’s a shack at the rear of the garden. If you decide not to stay — if you decide you don’t like our mugs — the gate is never locked.”

Fate often hangs on very little. Or rather, it is sometimes tied to a chain of events which bring you to your own personal moment of truth. Thus Flora’s white legs, dangling innocently from the edge of a fish-monger’s wagon, Fred’s fascination with them, the girl’s flight which followed, and the impossibility of returning to Les Halles all impelled Fred and Flora towards Belleville and the impromptu encounter with Rirette Maîtrejean and Victor Kibaltchich. And thus began the real adventures of Alfred Barthélemy.

Obviously, Fred and Flora did not remain sagely sequestered in the cabin at the rear of the garden waiting for their destiny to happen by itself. Every day they careened down the rue de Belleville to the heart of Paris, diverting themselves with little things, pilfering only the necessities from the store shelves, inventing practical jokes to play on the bourgeoisie and tormenting the beat cops. Fred missed Les Halles, but wasn’t sorry about trading it for Flora.

Whenever they’d spent several days without seeing Rirette and Victor, they began missing the couple and returned to their little nest in Belleville with a kind of gourmet gluttony. The devotion of these young people to each other fascinated them. It had the aura of a tender sensuality, mirroring the feelings Fred and Flora had for each other, only more ripe, more warm, in full blossom. Before they met this couple, Fred and Flora had no idea that happiness could exist.

Many men visited Victor and Rirette, usually in the evening or the middle of the night. Some of these men worried the children with their conspiratorial air. And Fred noticed something odd: Rirette and Victor addressed each other with the formal “vous” when they were alone and the less formal “tu” whenever their friends were around. The tutoiement in general didn’t surprise Fred; it was this private vouvoiement which intrigued him. (5)

All the visitors were very young, even if some of them could have passed for members of the bourgeoisie, like Raymond-la-Science, with his rosy complexion and doll-like visage, bowler hat, pince-nez, and dapper martingale jacket. Despite his diminutive size, Raymond-la-Science frightened the children. But as he never said a word to them, they eventually got used to the unexpected appearances of the “binoclard,” as they nick-named him between themselves, bursting into giggles. On the other hand, they became quite attached to a gentle, timid, green-eyed redhead who liked to recite poetry to them which he knew by heart. For example:

Hello, it’s me… me, yer ma

I’m here, standing before you in the bone orchard…

Louis?

My baby…. Can you even hear me?

Can you hear yer poor momma of a mother?

Yer ‘old lady,’ as you used to say.

Listening to these words, Flora’s fear dissipated. Like the child she was, she fell to blubbering. Fred would then stare at her, perplexed, not recognizing his cohort in this abandon, she who was always such a smart aleck and who adored leading him around by the nose. But the green-eyed redhead continued his plaint, which recounted the story of an old woman, come to the cemetery to look for the grave of her son condemned to die by the guillotine.

T’ain’t true, ‘tis it? T’ain’t true

everything they said about you at the trial;

In the papers, what they wrote about you

was all a pack of lies

And now that I see you here

Like a dead dog, a pile of refuse

Like a heap of manure, a mound of rotting apples

With the crème de la crème of criminals

Who is it who despite everything comes to see you?

Who pardons you and forgives you

Who is it who’s punished the most?

It’s yer old lady, you know, yer loyal mother,

Yer poor old lady, yer ragged old lady, look at me!

Fred didn’t cry. Fred never cried. But he was rattled.

“How do you come up with things like that?” he asked. “It has the ring of truth.”

“I didn’t come up with it, Freddy, it’s a poet. Jehan Rictus (6), remember that name. I know all his poems by heart. You could stand to learn a little poetry yourself. You can’t keep on living like a little savage. Look at our friend Raymond, he knows everything. That’s why we call him Raymond-la-Science. When you know everything, you can do anything. For Raymond, nothing’s impossible. Do you at least know how to read?”

“Yes.”

“Has Victor made you read our newspaper?”

“What newspaper?”

“How’s that? He hasn’t told you that we put out a newspaper? You haven’t seen him proofing large sheets of paper?”

“Ah, you know, the newspapers, I don’t trust them as far as I can spit.”

“Neither do we. Newspapers lie. Not ours. It’s called Anarchy. Rirette and Victor write the articles. I type them up, and in the basement, Octave works the printing press by hand.”

Octave Garnier? Him Fred knew. The brawniest of the nocturnal visitors – and the most sinister-looking. It was no surprise that he’d been stowed away in the cellar.

“And Raymond-la-Science, where does he fit in?” asked Fred.

“Raymond? He’s our treasurer. He figures out where to find the greenbacks. Because money’s essential to the cause. And there’s no shortage of money. Knowing where to recuperate it – and how to hold on to it – that’s where the science comes in!”

“I don’t like la Science,” Fred grumbled. “He’s a bourgeoisie, and he thinks he’s too good for us.”

The green-eyed redhead chuckled.

“Raymond, a bourgeoisie! If he could only hear you say that. It’s true that he looks like a bourgeoisie. But that’s what it takes to win the confidence of those who hold the purse-strings.”

The next day, the redhead, whose name was Valet (as far as Fred knew, he didn’t have a first name), lead Fred and Flora to the center of Paris and the Odeon neighborhood on the Left Bank, below the Luxembourg Gardens. Valet wanted to just bring Fred, but the boy refused to be separated from Flora. Valet grew irritated:

“Look, you’ll see her again tonight, your girl-friend. I don’t know how you can stand it, being around her so much, she doesn’t smell good. She’s going to stink up the shop I want to take you to.”

“It’s not true!” Fred shot back, indignant. “She does not stink, it’s the fish.”

“Fish?”

“She came to Paris on a fish-cart. It sticks to the skin, that odor. But it’s also the odor of the sea, no?”

“All right, as you like. It’s just that if you start out at such a young age attaching yourself to women’s petticoats, you’ll never stop drooling over them, my poor Freddy. But after all, it’s none of my onions.”

On the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, Valet ushered the two children into a small shop stuffed floor to ceiling with books. They were everywhere. On the shelves overflowing with paperbacks and hardbacks which blanketed the walls. Heaped up in piles on the floor. Try foraging a path through them, and one risked making the towers of print come tumbling down. Fred and Flora had never seen so many books. Rirette and Victor also collected books, but they kept them neatly arranged in wall racks. This flood of paper reminded Fred of the Paris inundations of the year before.

From this disaster zone miraculously emerged a weathered man with jet black hair, a mustache, and a goatee. He looked more like a factory worker, and his presence in this literary enclave seemed incongruous.

“Paul, meet Fred and Flora,” Valet announced. “They’ve been adopted by Rirette and Kibaltchich.”

“What are all these books for?” Flora asked with a disgusted air.

“Look around you, kids,” said Valet. “At the right, you’ll find novels and poetry. At the left, books about social issues and politics. On one side, dreams, on the other, action. When you have both at your disposal, you can take on the world.”

“Slow down, Valet,” cautioned the bookseller. “Don’t get carried away. It’s not so simple. Novels are also a form of social action and politics is also about dreaming. As far as taking on the world goes, the real question is: What will you make of it? What’s important is conquering oneself.”

“You didn’t always talk like that, Paul. You’ve holstered your six-guns because you’re getting old. In your time you were as much of a law-breaker as us. Remember Ravachol, and Vaillant’s bombing of Congress…?” (7)

“Vaillant was manipulated by the cops. They chopped his head off, but the real guilty party was the prefect of police. Don’t talk to me about Vaillant. You too Valet, you’ll wind up by falling for police provocations. What matters today is no longer bombs, no longer counterfeit money, nor direct action, stealing from the rich to give to the poor. The future lies with the unions and it’s with the unions that we’ll bring on the revolution, when we’ve learned how to impregnate unionism with anarchism and anarchism with unionism. The regeneration of both depends on this eventuality and this eventuality only.”

The debate between Valet and the bookseller went on for hours. They’d lowered their voices to the point that all Fred could make out was indistinct murmuring. In any case, he was too absorbed in what he’d just discovered to pay attention to their argument. He’d opened up a book called “Les Misérables,” and this book penetrated him immediately. He forgot about the bookshop, Valet, Belleville, and even Flora. He read with great difficulty, but with such intense concentration that the characters of the novel seemed to come to life inside him. It was as if he’d been lifted up from the Earth, in a sort of state of levitation, held captive by a benign spell. He’d never had this sensation before. When he was ready to leave, Valet had to physically shake Fred like he was trying to wake him from a dream. Fred held the book tightly between his hands, open, clutched against his chest.

Valet looked at the cover, then addressed the bookseller with a satisfied air.

“Hey Paul, look at this. The lad sure knows sure how to pick ‘em. He’s reading Father Hugo.”

“If he likes the book, he should take it with him.”

“No,” answered Valet. “I had my own agenda in bringing him here. Because he took the bait, I think you should be the one to reel him in, this handsome trout. Set aside ‘Les Misérables’ for him, mark the page and he’ll come back to find out what happens next. Maybe he’ll end up reading the entire bookstore and grow up to be as smart as Raymond.”

“Raymond’s head is not so solid. Science has warped it. He’s a well of science, that Raymond, but at the bottom of wells contaminated water sometimes lurks. Don’t drink the water, it will poison you.”

Valet shrugged his shoulders.

“Hey, look at the girl. She doesn’t give a fig about your science and your unionism.”

Flora, spread-eagled on the back of the bookshop’s gargantuan dog, who of course was named Gutenberg, was galloping around the place in a crescendo of giggles, overturning in her wake heaps of dusty books. Fred glared at her with such an air of reprobation that she exclaimed defiantly:

“You know what? Gutenberg and me, we can’t read, but that doesn’t prevent us from leading a dog’s life.”

Rirette and Victor lived at 24, rue Fessart. Fred and Flora devoted much of their time to exploring the neighborhood. Their immediate surroundings at first, the Place des Fêtes, with its music kiosk. By following the rue Fessart in the opposite direction, they came to a wondrous spot, the Buttes-Chaumont park. They always raced in as if they were afraid it was off-limits and they’d be barred at the last minute, not stopping until, out of breath, they found themselves standing on one of the wooden bridges straddling the chasms over the man-made gardens far below. They marveled at the waterfalls, the lake which wound around the park, the small temple of columns perched at the top of a 180-degree cliff, the caves and tunnels. It was at the Buttes-Chaumont that Fred discovered nature, weeping willows, pine trees, and streams, and his image of the country thus remained distorted for the rest of his life. When he finally found himself confronted with the real thing years later, it would be the genuine article which seemed aberrant and hostile.

The vast, steep, grassy slopes were made to order for frolicking. But as soon as they perceived, on the other side of the park, the high slate roof of the 19th arrondissement’s imposing municipal hall, they docilely fell into line and calmly executed a solemn exit. Until they bolted towards the rue de Crimée and arrived at their other major pole of attraction, the la Villette basin, bordered by warehouses. Sometimes they ventured as far afield as the banks of the Ourcq canal, lingering to watch the fishermen snoozing in their folding chairs. The barges, bistros for bargemen and dockers, the rotunda, the mounds of coal, all of this fascinated them. On the quays of the canal, Fred retrieved an ambiance which reminded him of Les Halles.

More and more frequently, Valet slept at the rue Fessart, bunking with Fred and Flora in the cabin at the rear of the garden. This exquisitely gentle, timid young man felt at home with the two children. When the winter brought with it rain and cold, Rirette procured shoes for Flora. Even though he didn’t particularly care for this little girl who just could not sit still, reserving his affection for Fred, Valet found her warm clothes. Fred preferred Valet over Victor, the latter putting him off him with his precious airs easy to mistake as contemptuous. For that matter, in the late-night debates Kibaltchich always seemed to hold back, as if the company of the three men who helped him put out the newspaper weighed heavily on him. Sometimes it even seemed like he didn’t trust them. In any case, during their animated discussions, in which the ideas eluded Fred, Victor rarely agreed with his companions. The tone would escalate, often up to and including threats. With her easy manner and smile, Rirette somehow always knew how to calm things down.

What surprised Fred and Flora was how different every member of the band was from all the adults they’d known before. All the men and women they’d previously lived amongst, starved for meat, chugged red wine by the gallon. But Rirette and Victor’s companions, like them, did not drink wine, didn’t eat meat, and didn’t smoke. They sustained themselves almost exclusively on vegetables, never adding salt, pepper, or vinegar to anything, and quenched their thirst with clear water. Only Victor sometimes betrayed aristocratic tastes, subjecting himself to the ribbing of his friends because of his penchant for drinking tea.

An ancient complicity linked Victor and Raymond-la-Science. They’d met as teenagers in Brussels, where the student Kibaltchich, born to a scholarly family of Russian exiles, had been fascinated by this petit proletarian, the son of a socialist shoe-cobbler. While his real name was Raymond Callemin, his thirst for knowledge rapidly won him the soubriquet in the revolutionary milieux of Raymond-la-Science. His intellectual passion was spiked with a predilection for violence that alarmed the Belgian socialists so much they finally banned him from the House of the People in Brussels. Vagabonding along the routes of Switzerland and France, Callemin-la-Science, by turns mason and logger, reunited with Kibaltchich in Paris and managed the purse-strings for Anarchy. A treasurer of an irreproachable probity. Not only had he never taken a penny from the coffers, but he somehow always found a way to make up for budget shortfalls. And it was exactly over the source of these funds that the discussions with Victor regularly turned sour.

Fred, who had often returned to the bookshop on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, had hungrily devoured “Les Misérables” and eagerly moved on to Eugene Sue’s “Les Mystéres de Paris” (8) and Emile Zola’s “Germinal.” Bit by bit, he began to understand some of what these exalted men were saying who seemed to toss theories at each other like other men might trade punches in a bar brawl.

In a somewhat imperious tone, Victor claimed that Kropotkine (9) himself had pronounced his own mea culpa, recognizing the sterility of “propaganda by the facts” and of direct action.

“It’s time to abandon bomb-tossing and turn the unions into practical schools of anarchism. Monatte (10) and Delesalle call for nothing less than this.”

“Illegalism, terrorism, total rebellion. There’s no middle ground. We are men of the Browning and of dynamite,” Raymond Callemin wrote. “We exploit all scientific progress (Ah, science! The word was always on the edge of his tongue!): the automobile, the telephone, anything which is quick and doesn’t leave a trace.”

“At least take some time to reflect…,” Victor insisted, exasperated.

“When you spend too much time reflecting, you never act,” Raymond retorted. “Long live impulsiveness!”

To which Octave Garnier, emerging from his basement and cradling his printing press in his thick arms, added, “Long live the outcasts, the wretched, the illiterate! In ‘The Rebel,’ Kropotkine extols the revolution of the riff-raff and the shoeless. Well, here we are! Watch your step, Victor, you’re just a bourgeoisie intellectual, a sentimental revolutionary. Those who aren’t with us are against us. Watch your step!

In December, Callemin, Garnier, and Valet suddenly vanished from the rue Fessart. Victor and Rirette seemed relieved. For Fred on the other hand, without Valet the cabin at the back of the garden became depressing. On top of this, Flora was sulking. Turning somber, her blue eyes took on a bizarre glaucous hue. Huddled in a corner of the cabin, swallowed up by her woolens to insulate herself from the cold, she resembled a frightened cat, ready to pounce, scratch, and bite. Fred read, by candle-light. He heard Flora grumbling.

“Are you sick? You have a weird look.”

“You’re the one who’s sick, Freddy. You don’t love me any more.”

Fred dropped the book and rushed to the girl’s side.

“Are you kidding or what?”

“No I’m not,” Flora whined, “you prefer the redhead. You follow him around like a faithful puppy. And now that he’s gone, you spend all your time reading. It’s as if I don’t exist.”

“You need to learn the alphabet, Flora. You’ll see how amazing it is. One discovers so many things, so many people, so many worlds. Ever since Valet took us to that fellow on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, I feel like I’ve grown ten years. It’s as if a curtain has come up on everything I didn’t know. I’m going to teach you to read, Flora. You’ll see. It’s as easy as saying ‘bonjour.’ We’ll read together.”

“Not interested! If I had any idea it would end up like this, I’d never have gotten off that fish-cart.”

“Don’t say things like that.”

He crept towards Flora, like a lion slowly stalking its prey.

“The big cat smells something delectable…. Whatever could it be? Ah yes, the scent of fish. But wherever could it be coming from, this fish odor? What’s this? Could it be a kitty-cat? No! It’s an over-stuffed teddy-bear.” Fred pawed at the thick wool stockings. Flora’s white legs re-surfaced and the boy sniffed them just like the first day, licked them, nibbled on them.

“Stop! You’re tickling me.”

“You still smell like fish. Or the sea.”

Flora seized Fred’s head in her small hands.

“Swear that you’ll always love me, Freddy!”

“I swear it. On Valet’s head, if it makes you feel any better.”

“Do you think we’ll love each other as much as Rirette and Victor, when we’re grown-up?”

“Just as much, yes. More isn’t possible.”

One evening in February 1912, as they were returning from one of their gambols along the la Villette canal, where they’d been admiring the ice-skaters, they found Rirette alone and completely shaken up.

“Ah, my petites, they’ve taken Victor away. I wasn’t all that surprised.”

“Who’s taken him away?” asked Fred. “Raymond-la-Science?”

“No, the police. Raymond and Octave did something stupid, and because the police know they’ve lived here, we’re in for it. As if things weren’t bad enough already, they found two pistols in the kitchen cupboard. Except for that, they don’t have a thing on Victor.”

“And Valet?”

“Valet, I don’t know. I hope they didn’t drag him into it. Somebody who’s normally so gentle, he wouldn’t hurt a fly. The problem for you two is that you can’t stay here any longer. The neighborhood is crawling with cops. I’m being watched wherever I go. I’m being tailed. If they spot you, they’ll find it odd. They’re capable of locking you up in juvenile hall, an orphanage, the poor house. Since you’re friends with Paul, ask him to help you out on my behalf. He won’t let you down.”

“Which Paul?”

“Paul Delesalle, the bookseller on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince.”

“Oh no! Fred will spend all his time reading the whole bookstore!”

Rirette quickly hugged Flora and Fred, pushing them towards the door.

“Go on now, les enfants, walk and don’t run. Calmly. Take your time. As if you were coming home from school. Good luck.”

Curious bookshop, Paul Delesalle’s. A first-class lathe operator, Delesalle had built the premiere movie camera for the Lumiere brothers when they invented the cinema in Lyon. On the other hand, the police listed him among “the hundred or so militants making up the French Anarchist Party.” Engaging in “propaganda by the facts” — in other words, terrorism — under the influence of Bakounine (11), for his whole life he’d be suspected of having taken part in the 1894 Foyot restaurant bombing, in which the sole victim was unfortunately the anarchist poet Laurent Tailhade, who lost an eye. But after the London congress of the Second Internationale, which terminated with the rupture between the Marxists and the anarchists, Delesalle, a disciple of Kropotkine, renounced terrorism in favor of anarcho-syndicalisme (12). After he’d worked steadily in factories for 10 years, in 1908 Delesalle’s passion for books inspired him to open, at 16 rue Monsieur-le-Prince, a singular bookshop consecrated primarily to revolutionary and labor publications. And it was here that Alfred Barthélemy would earn his Master’s in Humanities.

With his swarthy, somewhat sickly appearance and dry, gruff character, there was nothing about Paul Delesalle destined to please the two runaways. Already in his forties, in Fred and Flora’s eyes he seemed like an old man. But his companion, Léona, knew just how to tame them. It was nonetheless out of the question to put the pair up at the rue Monsieur-le-Prince. The space was made up of just two rooms, linked by a dark hallway. The bookshop occupied the first room, which gave on the street, while the second, which served as a bedroom and stock-room, had no ventilation except for the hallway, where one had to maneuver between walls stacked with publications constituting a veritable archives of the lives of workers and unionists, and which Delesalle bought for the price of old parchment at the auction houses. A rudimentary kitchen had been installed in a corner nook. Like all libertaires (13), the Delesalles lived a Spartan lifestyle, eating very little and drinking only water, more interested in filling their heads than their bellies.

Impossible, then, to accommodate Fred and Flora in this Capernaum. Gutenberg, the dog, already occupied the place of the child that the Delesalles had never had. Who could take care of them? Among the bookshop’s regulars, the poet Charles Péguy (14), a solid family man, might have some good advice to offer. Delesalle and Péguy, meeting up in the midst of the Dreyfus Affair, when they joined forces during the scuffles against the anti-Semites, had never stopped frequenting each other since and addressed each other in the familiar ‘tu’ form. Several times a week Péguy stopped in at the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, enveloped in his black cape, his close-cropped hair lending him the air of a defrocked monk, his long beard and his pince-nez masking his tiny blue-gray eyes.

Charles Péguy enthusiastically rallied to the idea of extracting the pair he immediately baptized Gavroche and Eponine from the creek.

“Gavroche is okay for me,” Fred grumbled. “But Flora isn’t any Eponine. She’s Flora, period.”

“What’s this?” exclaimed Péguy. “This little sparrow has read ‘Les Misérables’?”

“He read it in the shop,” Delesalle explained. “He’s even got it into his head to stay here until he’s devoured every book in the place.”

“You couldn’t do that in a lifetime, my son. And it’s not enough to read, you have to act. How old are you?”

“Thirteen.”

“You need to work with your hands, at the same time cultivating your mind. An educated mind and a worker’s hands, nothing’s more beautiful than that! What trade would you like to learn?”

“Typography.”

“Typography…. Ah! Yes, it’s good work. Perpetuating the work of the thinker by transforming it into lead characters, which then multiply and spread the word like manna from Heaven….”

“Yes, typography,” Fred repeated confidently. “Typography, like Valet.”

“Valet? Who’s Valet?” Péguy asked.

Delesalle murmured: “A member of Bonnot’s gang.”

Péguy threw his hands up. Tossing his cape behind him, he assumed the air of a lawyer admonishing the court.

“So much wasted energy! So many ideals perverted!” His hands fell on Fred’s shoulders.

“Okay, I’ll take care of the boy. As for the girl, you can entrust her to Sorel (15).”

“To Monsieur Sorel?” Delesalle sputtered. “But he won’t know….”

“You can’t break up me and Flora,” Fred protested.

“I was just kidding,” Péguy assured them.

Enveloping the two children in his cape, he pushed them along in front of him and left the bookshop with the air of an evangelical shepherd.

The Péguy episode didn’t last long. Flora fled the second day and Fred took off after her. He finally found her near the la Villette rotunda. As she’d been brawling with hooligans who wanted to haul her off to the ancient fortifications, the new clothes Valet had given her were cut to shreds. She had only one shoe left, having used the other to fend off her attackers. A tuft of her blonde locks had been torn out and her lower lip was split and bleeding copiously.

Fred took her gently by the hand, lead her over to the Wallace fountain, and scrubbed her face. Unable to walk with only one shoe, she tossed it and found herself once again bare-footed.

Without saying a word, they meandered together along the streets, inevitably ending up on the rue Fessart. Rirette welcomed them without surprise and without reproach. Still charming, but sad and anxious.

“Don’t say a word. Yes, you’ll retrieve your cabin at the back of the garden, but not for long. They’ve left me free because they’re tailing me. They think I’ll lead them to the ringleaders. Once they’ve found them, they’ll lock me up with Victor. All of this is not healthy for you. Your only resort is Delesalle. He at least is not compromised. No one else is safe.”

“When’s Valet coming back?”

“Valet? Never. Not him, nor Garnier, nor Callemin. You mean you don’t know? That’s right, you don’t read the newspapers. Take a look at this.”

On the table, where Fred had so often seen Victor Kibaltchich looking over the printer’s proofs for Anarchy, Rirette had spread out the editions of the Excelsior from the last several days. Banner headlines jumped out at him: “THE BANDITS AT THE WHEEL,” “BANK COURRIER ATTACKED AT 8 THIS MORNING ON THE RUE ORDENER….” A front page cartoon depicted a man wearing a baseball cap with ear flaps, brandishing a pistol, a cashier in a bicorn hat and jacket collapsed in front of him.

“The guy with the pistol looks a lot like Garnier,” Fred remarked.

Next, Rirette showed him a paragraph on the inside pages of the newspaper. There, the reporter described “a man who seemed quite young, not very tall, wearing a martingale jacket and coiffed with a bowler hat, sporting a pince-nez and with the rosy complexion of a baby.”

Fred was stunned. “The spitting image of Raymond-la-Science.”

“Now look at this front page from the Petit Journal.”

It was dominated by a full-page spread on the bank attack: Overturned chairs, employees shot at close range by attackers who had scaled the counter. Once again, Octave Garnier was clearly identified by his famous baseball cap with ear flaps, as was Raymond Callemin with his bowler hat and pince-nez. And there, filling up a sack with bright coins.…

Fred put his finger on the photo. “Valet?”

“Maybe,” answered Rirette. “But if you were able to recognize them so easily, you can imagine that the cops must already have their number. All they have to do now is lay their hands on them. Which won’t be easy! They know that the guillotine lies at the end of their adventure. They’ll defend their hides until their last breaths.”

“Delesalle didn’t want me to hear him. But I remember him talking about the ‘Bonnot gang.’ Is that them?”

“One day, Raymond introduced us to a short, stocky man with a red mustache, Jules Bonnot. Mechanic, car thief, hot-rodder, he claims to be an anarchist, but in fact he’s just a thug who uses anarchy as a pretext. Victor and I constantly warned Garnier and Callemin about this blow-hard. But they were hoodwinked by him. And voila the results.”

“But if Victor didn’t agree with them, why have the cops locked him up?”

“To make him squeal. But Victor and I aren’t rats. We won’t say a word. Even if we don’t agree with their tactics. We don’t agree with Bonnot but we also don’t agree with Lépine (16). But – and always remember this, my petit — the hooligans and the cops are both gun-slingers. Avoid the one and the other like the plague. Always.”

The rue Fessart smelled too much like cops for Fred and Flora to be able to remain tranquilly in their refuge for long. They therefore migrated once more to the Left Bank. Fred proposed that Delesalle hire him as his messenger boy, in exchange for daily rations of Léona’s soup.

“But what about your girlfriend? And where will you sleep?”

“That’s my business,” Fred replied. “Don’t worry about it.”

In a square on the boulevard Saint-Germain he’d noticed an abandoned construction office. It would replace the cabin on the rue Fessart. The fences around the square, not that high, could easily be scaled at night. Fred and Flora adopted it as their new home. Flora found work as a pearl-diver in a restaurant, in exchange for meals. Fixed as they were for grub and with a roof over their heads, the spring of 1912 began auspiciously for the infants.

Every morning Fred accompanied Delesalle on his rare book expeditions. He canvassed the length of the quays on both sides of the Seine, digging in the boxes of the bouquinistes (17) and extracting original editions not yet considered rare: Jules Renard’s “Histoires naturelles,” illustrated by Toulouse-Lautrec; a first edition of Paul Verlaine’s “Sagesse.”

“You have to read Verlaine,” Delesalle urged Fred. “He’s our most important poet. I used to roam the narrow streets of the Latin Quarter with him, when I was younger. Because I didn’t drink, he relied on me to get him home when he was falling down drunk.”

“Valet taught me Rictus’s poems…. ‘La Jasante de la vielle…’ He’s just as good, Verlaine?”

“Rictus, Couté (18), yes, they’re good. But Verlaine’s better.”

Whenever Delesalle found a book he particularly loved, he insisted Fred read it. A strong bind was soon forged between the mature man and the child. Intelligent, quick-witted, and possessing a phenomenal memory, Fred was able to unearth obscure brochures which enriched the bookshop’s collection. All the names of revolutionaries, of labor activists, were rapidly etched into his brain. None of these authors escaped his eye, neither in the bouquinistes’ stocks nor in the auctions at the Hôtel Drouot (19). Delesalle was amused by his enthusiasm. As he was by Fred’s bulimic reading.

In reality, Fred spent more time reading, curled up on the floor in a corner of the bookshop, than helping the man who was never really his boss, but rather his initiator and, as it might be put in more refined circles, his mentor.

He loved just hanging out in the neighborhood. The rue Monsieur-le-Prince mounted, in a more or less straight line, from the Odeon to the boulevard Saint-Michel. Delesalle’s shop was located mid-way between them, right where the horses’ hitching-posts began and the snorting of the beasts started up. The coachmen cursed and cracked their whips. Fred sometimes helped push the carts along. On the other side of the street rose an immense building, with high wide frosted windows, which intrigued him. He circumvented it by descending the stairway which let out on the other side on the rue de l’École-de-Médicine. On the facade, intrigued, he read, “École Pratique.” Practice of what? He wanted to learn every practice!

On May 15, 1912, the French army, which had not yet recovered from the humiliating defeat of the 1870 war with Prussia, finally scored its first victory, a kind of prelude to the wholesale butcher shop which would soon be open for business. At dawn, two entire companies of Zouaves (20), illuminated only by acetylene headlights, launched an offensive on a pavilion house in the Paris suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne. Before starting the assault, they breached the millstone walls with three sticks of dynamite. As this modest hovel still seemed foreboding to them, they then set off melinite explosive charges and riddled the windows with a riot of machine-gun fire. When the soldiers finally decided, with infinite precautions, to penetrate the interior of the hut, they found themselves face to face with a man bloodied all over, his torso naked, and who still had time to get off four shots before he was mowed down. Valet. Garnier was discovered squeezed between two mattresses, having killed himself with a bullet in the mouth.

That same morning, when Fred arrived as usual at around eight at the bookshop on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, all the newspaper headlines were screaming about the night’s tumult and the formidable bravery of the forces of order. But Fred never read the newspapers. Delesalle did not know how to break the news about Valet to him. So much so that this delicate man, normally so sensitive to others’ feelings, after struggling to come up with the least painful way to explain what had happened, finally blurted out in the most brutal manner possible:

“Fred, I need to tell you something, it was bound to end up like this, they’ve liquidated the Bonnot gang. Bonnot, Garnier, Valet, they’ve escaped the guillotine, but not their punishment. As we’re speaking, they’re all dead.”

Fred hurled like a wounded animal, letting out a yowl so piercing that Léona came running and Gutenberg began to howl in solidarity.

“They’ve killed Valet!”

“Valet killed innocent bystanders, my petit,” Léona responded gingerly. “We all know he was a gentle soul, an idealist, but he let himself be manipulated by criminals.”

“How did they kill him?” Fred demanded, clenching his fists.

“He defended himself to the end,” said Delesalle. “He fought off a company of Zouaves. In a ‘just war,’ as our friend Péguy might put it, he’d be hailed as a ‘hero.’ But there’s no such thing as a ‘just war.’”

Fred tore out of the bookshop before Delesalle could stop him. Leaping onto the rails of a cart trotting up the boulevard Saint-Germain, he coasted along until the Sully bridge over the Seine, then hopped off to scurry by foot towards the Bastille and after that, Belleville. On the rue Fessart, he found the gate to Victor and Rirette’s house padlocked. He nevertheless pushed at it, felt himself gripped by the arms and turned around to see two giant beat cops who began shaking him, as if they wanted to make who-knows-what key fall from the boy.

“Why do you want to enter this house?” the first one asked.

“I know a lady who lives here. I just wanted to pay my respects.”

“’A lady,’ one of the cops sneered, “how you go on! And what’s her name, your ‘lady’?”

“Rirette.”

“’Rirette’? That’s no name for a lady, that. Sounds more like a whore’s name to me.”

The cop received such a sharp kick in the tibia that he let out a yowl and released the boy. The second policeman, bitten in the hand, started to yelp. While this sob-fest was going on, Fred cut out towards the Place des Fêtes.

Re-descending the rue de Belleville towards the center of Paris, he headed for the dive where Flora washed dishes, penetrated the establishment, and made straight for the kitchen, whistling to his companion who, just as quickly, removed her smock and rushed to him.

“Come on Flora, we’re getting out of here.”

“Finally,” said Flora, “we’re going to make a life together.”

Then they left the restaurant together, hand in hand, without hurrying or looking back, to the general stupefaction of the customers.

Fred and Flora were once again roaming wild. It seemed to Fred that in cutting his ties with his honest job at the bookshop, in severing all links with society, he was in a way taking revenge for Valet’s death. He would have liked to have gone farther. Biting a beat cop made him feel a bit better, but he wanted to kill all of them. However he was smart enough to realize that this was beyond his means. Stealing, on the other hand, would enable him to flirt with prison, which would bring him closer to Rirette and Victor. So he became a thief. A small-time thief. A shop-lifter. Just enough to score bread, salami, shoes for Flora (unfortunately too big), a knife, canned sardines. Just enough to stoke the fear of getting caught. Just enough to shudder when a shop-keeper realized he’d been robbed and screamed bloody murder in the neighborhood.

Fred and Flora acquired a taste for petty larceny, a dangerous game that one refines with

dexterity. The fact is that for the very first time in their lives, they were having fun. They lived freely like alley cats, never sleeping in the same spot, getting to know every square in Paris by heart, sometimes letting themselves be locked in churches for the night, or the Luxembourg Gardens, or even the Montmartre cemetery.

Early one morning, as they were getting their act together after a night in a barrack on the fringes of the Montparnasse train station, they heard the galloping of hob-nailed shoes and looked up to see two policemen running after a bearded citizen with reams of hair streaming out behind him like a comet. Without consulting each other, they instinctively made for the cops. Fred sent the first flatfoot tumbling by thrusting his leg out and tripping him, while Flora barreled head-first towards the voluminous belly of the second who, in trying to avoid her, stumbled and flattened out on the pavement.

The two children raced after the comet-man, who sped down the rue de Vaugirard in the direction of the Luxembourg Gardens before turning into an dead-end street and vanishing, as if swallowed up by the Earth. Fred and Flora couldn’t care less about the man, but they were baffled by this irreal disappearance. Suddenly they heard a light whistle, which seemed to come from a basement vent. They walked towards the sound. The man was there, just behind the bars, and handed them a brand new one-franc coin which glittered in the early morning light.

Fred and Flora had never possessed so much money in their lives. So they didn’t even know what one might buy with a whole franc. For that matter, why buy at all, when it was so easy and exciting to steal? But because for once they’d actually earned this franc, they thought they might as well spend it. They entered a boulangerie, posed the coin on the counter and ordered an extra-large baguette. The boulangeriste considered the coin, weighed it carefully in her hands, placed it between her teeth, bit into it as if she were going to eat it, then removed the coin from her mouth, completely warped. At the same time she cried “Thieves!” loud enough to rouse the entire neighborhood.

Dumbfounded, Fred and Flora amscrayed, confused about why they’d been treated like thieves the first time in their burgeoning lives they’d decided to do something honest.

From hanging out in the streets, Fred inevitably ran into Delesalle, bowed under the weight of an enormous bundle. “What are you carrying there?”

“Books, of course, my boy; what, you expected silverware?”

Delesalle was on his way back to the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, his used book buying done for the day.

“And you, Fred, what’s become of you?”

“I almost got pinched because of a character who slipped me 20 cents.”

“How’s that?”

“The coin was counterfeit. So it’s true that anarchos fabricate their own money? I read that in one of your books.”

“This was the case during the epoch of illegalism. But it doesn’t make any sense today. No more sense than the Bonnot gang. I once knew a counterfeiter who was a solid harness-maker in his time. He earned 60 francs a week. These days, he works like a dog to mold coins that he can’t even get rid of, they reek so much of counterfeit. He earns at most 30 francs, half as much as he made when he was an honest man, and will probably finish his days in the Cayenne penal colony. Listen, Freddy, come with me; come back to the shop. I’ll make a good worker out of you and a useful revolutionary. You’ll learn that rebellion doesn’t lead to anything. Only the rebel who’s transformed himself into a revolutionary is useful. You started out so well. You don’t miss the books?”

“I do.”

“Rirette and Victor come up for trial on February 3. Between now and then, we need to make a man out of you.”

Fred plunged once again into the sea of books. Every morning he went trolling for rarities with Delesalle. They looked just like ragmen with their arms lugging patchwork canvas sacks which gradually filled up with their bounty as the day progressed until, packed to the brim, they hauled them back to the shop. The boy like the man thrived in this treasure hunt for yellowed paper. And this on top of the surprises from the auctions of bundled lots where, in the mystery trunks acquired, they sometimes unearthed brochures without any commercial value, but which Delesalle considered the pride of his catalogue. Because five times per year the miniscule, somber shop on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince published a catalogue entitled “Publications on Social Movements,” and subtitled, “Bibliographic compendium of all documents relative to social movements in France and abroad.”

In the afternoons, Fred classified, indexed, and above all read for his own edification. Delesalle let him. Watched him. He had his own agenda. But he didn’t want to rush things. Léona and he simply arranged things so that the two children were rescued from their vagabond life and all the dangers of corruption that this engendered. After all, Péguy had given them a good idea. Flora could help out in the household of “the venerable Sorel” who, widowed, lived with his nephew. She’d thus get on-the-job training in cooking, house-keeping, grocery-shopping. And in exchange, the venerable Sorel would put Fred and Flora up in his pavilion house in the suburb of Boulogne.

Flora didn’t entirely appreciate this arrangement, running away several times, but in the end, the venerable Sorel’s good will won out over her innate savagery.

It wasn’t his impressive 66 years that earned him the honor of being referred to as “the venerable Sorel,” but that everything about him — his stature, his allure — leant him a patriarchal air. Ever since his rupture with Péguy, which meant he no longer had access to the offices of the latter’s Cahiers de la Quinzaine (21) , every Thursday Sorel held forth in Delesalle’s bookstore. Thus while Delesalle’s rapport with Péguy was familiar (although Péguy certainly wasn’t imagining things, contrary to what his enemies at the Sorbonne said, when he vaunted himself as a man of the people), his relationship with Georges Sorel was marked by an unusual veneration, leading the militant revolutionary to insist on addressing the philosopher as “Monsieur Sorel,” or, even more unusual coming from the mouth of a libertaire, “Maître.” (22) (Although after all, it wasn’t the anarchist Proudhon (23) but the socialist Blanqui (24) who came up with the famous slogan, “No God, no Master.”)

With his broad forehead, crowned with white hair, his staccato manner of speaking, and his adoring public who packed Delesalle’s bookshop every Thursday, Sorel fascinated Fred, even as he unnerved him. His speeches, religiously followed by a small audience which combined manual laborers and intellectuals, his indefatigable peroration, and the assurance with which he assumed the posture of maître, annoyed the child, who ended up considering him an incredible bore. Above all he resented the older man for accepting that Delesalle address him as “maître”; he resented Sorel for this failing on the part of Delesalle, for this default in the bookseller’s otherwise impeccable rigor. The only thing that amused him was the way the man whose admirers compared him to Socrates ruffled his beard when he reflected.

In fact, it took all of Delesalle’s kindness, authority, and powers of seduction to make Fred, despite his passion for books, remain confined in this small shop in which the only furniture consisted of Paul’s writing table and Léona’s cash register. The rue Monsieur-le-Prince, into which sunlight rarely penetrated, was in and of itself sufficiently morose. No resemblance to the boisterous animation of Les Halles, nor the working-class familiarity of Belleville.

In this dusty, calm atmosphere (too calm for a 13-year-old accustomed to the hustle and bustle of the streets), Fred felt that he was getting stiff. Without doubt he would not have lasted much longer cooped up on the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, had not the dramaturgy of the courtroom opportunely arrived to shake things up.

With Bonnot, Garnier, and Valet eliminated by the forces of order, the sole original member of the gang still alive was Callemin, or Raymond-la-Science, the only one who was able to be captured by surprise. The government, hoping to set an example, had succeeded in inculpating some 20 individuals under the pretext of the charge “association des malfaiteurs,”or criminal association. (25) By virtue of this accusation, Rirette and Victor occupied the place of honor, the judges regarding them as the kingpins of the Bonnot gang because the offices of Anarchy had served as the lair of the ‘tragic bandits.’ Appearances were against them.

Despite that very few members of the public were allowed into the courtroom, plainclothes policemen taking up most of the seats as a precautionary measure, Delesalle had succeeded in getting admitted to the Hall of Justice, accompanied by Fred. The banks of the accused had to be expanded to accommodate the 20 defendants, with each flanked by a pair of gendarmes. They were all young, the median age being around 25. Fred immediately looked for Rirette and Victor. He was astounded to discover a Rirette still fresh-faced, smiling, with her black blouse, Peter Pan collar, and floating ascot tie making her seem all the more juvenile and mischievous. Close to her, Victor Kibaltchich held up his thin silhouette: clad in the traditional Russian peasant smock which constituted his habitual costume, he stood out as the most elegant member of the gang. The most serious as well. Farther along down the line Fred recognized Callemin who, divested of his martingale jacket, bowler hat, and pince-nez, looked like a junior high school student.

Smiling at the judges and jury, Rirette, with her vivacious voice, quickly demonstrated that neither she nor Victor had sullied their hands in any of the reprehensible deeds of the Bonnot gang. She drew the obvious sympathy of the court, even though it was still angling for its wagon-load of culpables. But Victor somewhat spoiled things with his eloquence. As when the chief judge, annoyed, launched:

“What are you complaining about? You are a foreigner, banned from your own country, free to express your own ideas in ours, and yet you somehow find a way to welcome assassins into your home. You’ve been arrested, as is normal, but you’ve not been mistreated. Have we tried, by unacceptable methods, to extirpate a confession from you?”

“I’m not complaining about the gentleness of your police, Monsieur le judge,” Victor answered in his serious, measured voice. “On the contrary, it’s your amiability which worries me. Monsieur Jouin, deputy chief of security, did not address me familiarly, nor rudely. He simply wanted me to become his accessory.”

“I’ll thank you not to take the name of a dead person in vain,” the judge exclaimed. “Monsieur Jouin died in the line of duty, assassinated by your friend Bonnot.”

“Bonnot was not my friend.”

“But Callemin, on the other hand, was.”

“He worked with our printer, before this business. I’m in solidarity with anarchists, not murderers.”

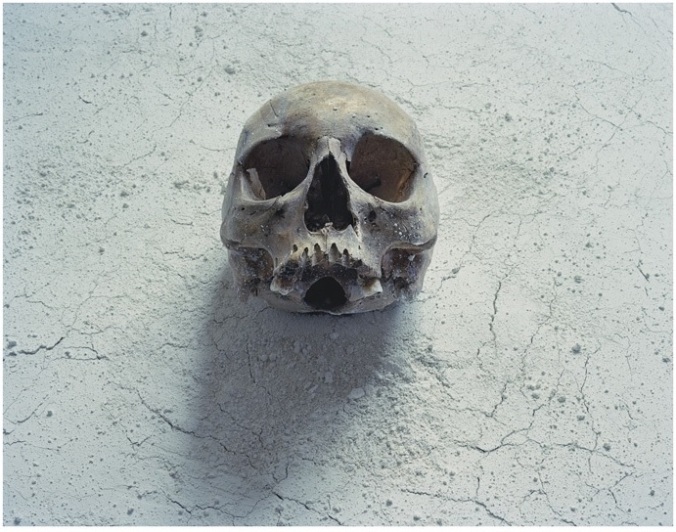

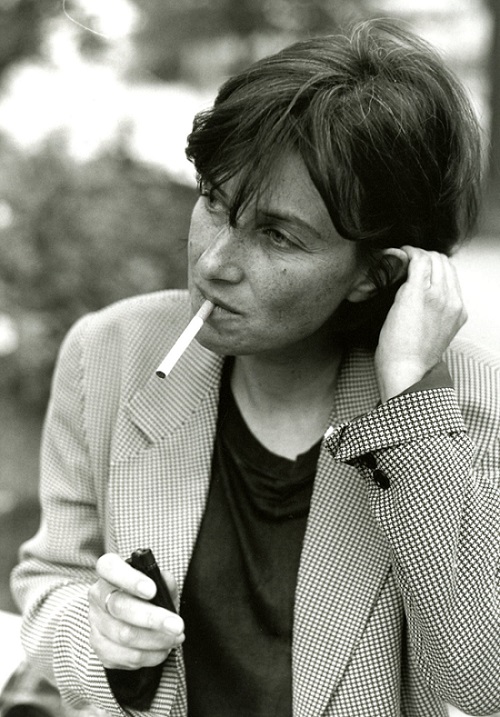

The chief judge, with his round bonnet, his mustache and thick beard, his crosses, and his bib, looked like a judge that might have been painted by Georges Rouault, half-judge, half-clown.

George Roualt (1871 – 1958), “Clown de Profil,” 1938-39. Oil on paper laid down on canvas, 80 x 58 cm. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

“What distinction do you draw between an anarchist and an assassin?” the judge pressed. “Wasn’t Bonnot an anarchist?”

“I repeat that the ideas that I’ve stood for all my life do not sanctify thieves and murderers,” Victor responded softly. “We’re accused of being the pivot of a criminal organization. I remind you that we have always been poor, that we had to ask for donations just to be able to publish our newspaper. We have no judicial antecedents. We’ve not killed, nor stolen, nor participated in any of the deeds of which the tragic gang is accused.”

The supreme judge-clown soon lost interest in Victor, whose reasoning, too intellectual, irritated him. He turned towards Raymond-la-Science who, from the beginning of the trial, had brandished a mocking smile.

“Your name is Callemin?”

“Yes, I haven’t changed it since yesterday.”

“What did you mean the day when you told an inspector: ‘My head’s worth 100,000 francs, while yours is only worth seven cents’?”

“Well, 100,000 francs, you’re the one who put that price on my head, and I presume that, in good faith, you paid the louse who denounced me. As for the seven cents, that’s the price of a Browning bullet.”

The room erupted with laughter.

His hair glossed down, his complexion more ‘baby rose’ than ever, Callemin flouted the court, the jury, the audience. As the chief judge enumerated his crimes, he interrupted:

“I’d also like to confess that it was I who strangled Louis XVI.”

A little later, cutting off the state prosecutor Fabre, stiff as justice in his ermine-trimmed velvet robe, he yelled:

“You’re just delivering a monologue! It’s all about you.”

The criminologist Emile Michon, who, during the nine months of the preliminary investigation, made frequent visits to the accused, testified next. Peculiar testimony, so different than what one might expect from such a man.

“Before I met the accused,” he said, “I thought of them as ferocious animals or, at least, genuine brutes. I was thoroughly surprised to discover men capable of analyzing their sensations and feelings with finesse. Because they like studying, they’re able to endure their detention much more easily than other prisoners. But what surprised me the most was their insensibility to the rigors of winter. When I asked to see them during visiting hours, they’d show up with their shirts unbuttoned, bare-chested. Always exhibiting an exemplary cleanliness, their hands freshly washed, their nails filed, this is how they stood out from the other prisoners, who are usually self-neglected, freezing whiners. Vegetarians who stick to water, every day they practice Swedish gymnastics.”

After this odd homage to the prisoners’ exemplary hygiene, the criminologist Michon added that Callemin had confided in him his yearning to steal an airplane, to pilot the vehicle and descend back to Earth. And he concluded, in a sweeping oratorical gesture:

“With such a mentality, it’s no surprise that this man should end up involved in some kind of crazy adventure!”

During the four weeks the trial lasted, Delesalle made sure that he and Fred witnessed most of the sessions. He wanted the sinister and theatrical images from these proceedings to be burned into the memory of the child. He wanted him to hear the horrible indictment being delivered by the state prosecutor. He wanted him to witness Callemin being sentenced to death, Rirette being acquitted, and Victor copping five years of prison simply for refusing to be a rat. He wanted this tragi-comedy to serve as a prelude for what he was going to tell the child.

Meanwhile, Flora, well-nourished, spoiled, coddled in the venerable Sorel’s house, expanded. She got a little bit taller, but most of all more curvy. So much so that Léona grew worried and took her to the doctor, who exclaimed joyously, as if it was a good joke:

“But…. this child is going to have a child!”

“My goodness,” said Leona, “better soon than never. Ah! What a funny pair, these two petits!”

Léona and Flora shortly rushed to the rue Monsieur-le-Prince to announce the news.

“What will you name him?” Delesalle asked Fred.

“If it’s a boy, I’ll call him Germinal.”

***

1. A church in whose choir another waif once sang, under the direction of Charles Gounod, who would regret that his pupil with the voice of an angel chose painting over music: Auguste Renoir.

2. French for “fish-monger.”

3. “Les Deux Orphelines” (The Two Orphans) was a five-act drama by Adolphe d’Ennery and Eugène Cormon which opened on January 20, 1874, at the théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin on the Grands Boulevards, and which the authors later adopted as a serial novel published in the newspaper La Nation in 1892 and in its entirety by Rouff in 1894.

4. “Belleville” translates as “Beautiful city.”

5. A thorough explanation of when the French use the familiar ‘tu’ and when they use the formal ‘vous’ could furnish enough material for a doctoral thesis. For the case in question here, suffice it to say that in their preference for the ‘vous’ even in intimate settings, the anarchists Rirette Maïtrejean and Victor Kibaltchich are joined by former French right-wing president Jacques Chirac and his wife Bernadette, among others.

6. Born Gabriel Randon, Jehan Rictus (1867-1933) was known for works written in the street language of his Paris epic, compiled in two books, “The Soliloquies of the Poor” and “The People’s Heart.” The poem translated on page 11, “La Jasante de la vielle,” begins: Bonjour, c’est moi…moi, ta m’man / J’ suis là, d’vant toi au cimetière…/Louis? / Mon petit… m’entends-tu seulement? / T’entends-t’y ta pauv’ moman d’ mère? / Ta Vieill’ comme’ tu disais dans l’temps. (See link in chapter above for more information as well as complete versions of the poems, in French.)

7. François Claudius Koënigstein (b. 1859), a.k.a. Ravachol, was a worker and anarchist militant. Judged guilty for several infractions, assassinations, and attacks, he was guillotined on July 11, 1892. Born in 1861, the anarchist Auguste Vaillant’s December 9, 1893 bombing of the French house of representatives, which wounded several people, bought him a date with the guillotine on February 5 of the following year and spurred the adoption by French deputies of a series of laws targeting the anarchists.

8. Initially published in 1842-43 as France’s first serialized novel, “Les Mystéres de Paris,” the story of a rich prince’s efforts, often incognito, to save denizens of the lower depths of Paris, anticipated Hugo’s “Les Misérables.” Eugene Sue (1804-1857) also served as a French deputy, and the novel is footnoted with references to legislative studies providing a social context and factual firmament for Sue’s character studies.

9. Piotr Alexeievitch Kropotkine (1842-1921) was a Russian revolutionary and anarchist. Founder of the Geneva-based anarchist newspaper La Revolte in 1879, he authored books analyzing the scientific bases of anarchy as well as looking at related economic and ethical considerations.

10. A printing corrector by trade (many French anarchists worked in printing — the real Rirette Maitrejean would later go into this trade), Pierre Monatte (1881-1960) was an anarchist and, later, revolutionary union activist and leader. in 1909, he co-founded the newspaper The Worker’s Life and, in 1925, The Proletarian Revolution.

11. Mikhail Alexandrovitch Bakounine (1814-1876), a major Russian revolutionary anarchist activist and theorist, was the author of “Statism and Anarchy “ (1873), and a fervent support of the 1871 Paris Commune.

12. Syndicalisme is the French equivalent of Unionism or Labor activism and organizing.

13. If the literal translation may be “libertarian,” this word does not have the same sense and implications in American English as it does in France, where it’s a more polite umbrella term for non-violent anarchism, encompassing even mainstream thinkers like Albert Camus.

14. A complex figure in the French literary-political landscape, if he began his career as a pupil of Socialist leader Jean Jaures, rallying to the cause of Captain Dreyfus, by 1900 the poet Charles Péguy (1873-1914) had drifted away from many of his Socialist colleagues, disagreeing with their anti-clericism and anti-militarism. His increasing nationalism lead him to declare, during the build-up to World War I (as cited by Max Gallo in “Le Grand Jaures”), “From the moment war is declared, we’ll haul Jaures before a firing squad,” Jaures having become the leading opponent of war. On July 31, 1914, Jaures was assassinated. Péguy himself would perish at the front later that same year.

15. As described in the “Petit Robert” French encyclopedia (1989), Georges Sorel (1847-1922) advocated an ethical socialism. To liberalism and Democratic “reforms,” Sorel “opposed anarcho-syndicaliste perspectives, seeing in violence, in particular the general strike, the crystallization of the class struggle and in social doctrines the ‘myths’ expressing the aspirations of the proletariat. If Sorel’s theories influenced revolutionary unionism, they were also exploited by the most reactionary movements, particularly in fascist Italy.”

16. Louis Jean-Baptiste Lépine (1846-1933) was the originator of the French criminal brigade.

17. Booksellers along the Seine, whose ranks have included Michel Ragon.

18. Like Rictus — see footnote 6 – Gaston Couté was a poet who sometimes incorporated the local patois. He also contributed to the libertaire newspapers “The Barricade” and “The Social War.”

19. Paris’s central auction house.

20. Part of the Foreign Legion, typically composed of soldiers from colonized countries in Africa and the Maghreb, such as Senegal and Morocco.

21. Founded by Péguy in 1900 at 8 rue de la Sorbonne to address political issues, the Cahiers de la Quinzaine published principally Péguy’s own oeuvres but also work by Romain Rolland and others.

22. Lit. ‘master’; in scholarly or artistic circles, a way to recognize the person’s authority in the given domain.

23. Described in the Petit Robert encyclopedia (1989) as the “father of anarchism, unionism and federalism,” Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) appeared to be “at the same time a revolutionary and, according to Marx, a conservative ‘petit bourgeoisie’ constantly racing between Labor and Capital, between political economy and Communism.’”

24. A socialist theorist and revolutionary, Auguste Blanqui (1805-1871) was arrested numerous times between 1831 and 1871 opposing various governments. In 1877, he launched the newspaper Ni Dieu ni Maiïtre. (Lit.: Neither god, nor master, but the sense intended here was more likely “No god, no master.”)

25. In 2018, the criminal charge association des malfaiters (literally “association of evil-doers,” the phrase can be translated as “association in a criminal enterprise”) was still being invoked in France, and winning convictions, often in terrorism cases where there were no other charges – where no other criminal acts had actually been committed. In April 2018, the fiasco of the State’s pursuit of the so-called “Tarnac Group,” in which after 10 years authorities had been forced to reduce charges of belonging to a terrorist enterprise to “association des malfaiters,” were finally dismissed when the judge proclaimed, in essence, that the ‘malfaiters’ organization in question – the “Tarnac group” – did not exist and was therefore a “fiction.”

Version originale (partial excerpt of the part translated above) par Michel Ragon

“Mais moi, je suis un pauvre bougre ! Pour nous autres, c’est malheur dans ce monde et dans l’autre, et sûr, quand nous arriverons au ciel, c’est nous qui devrons faire marcher le tonnerre.”

— Georg Büchner, “Woyzeck.”

Tous les matins, le froid réveillait l’enfant à l’aube. Bien avant que ne s’éteignent les réverbères, dans la pâle lumière grise, il s’ébrouait en quittant l’encoignure où il avait dormi, toujours au même endroit, dans une ruelle qui longeait l’église Saint-Eustache. Il s’étirait comme un chat, se secouait les puces, et comme un chat partait à la recherche de quelque nourriture, au pif, à l’odeur. Les Halles se réveillant en même temps que lui, il ne tardait pas à découvrir quelque chose de chaud. Les marchandes de volailles n’ouvraient pas leurs étals avant d’avoir discuté autour d’un bol de bouillon. L’enfant recevait sa part. Puis il s’éloignait en sautillant, jouant à cloche-pied entre les baladeuses chargées d’un amas de victuailles. Tous les vendredis, il remontait la rue des Petits-Carreaux, allant à la rencontre des charrettes de poissonniers qui arrivaient de Dieppe. Il aimait cette odeur d’algues et d’écailles qui déferlait vers le centre de Paris. La mer, cette mer qu’il n’avait jamais vue et qu’il imaginait comme une inondation terrible, se frayait un chemin à travers la campagne et descendait des hauteurs de Montmartre. On entendait les charrettes de très loin, dans un grondement de tonnerre. Les roues cerclées de métal faisaient sur les pavées un vacarme du diable. Auquel s’ajoutait le cliquetis des fers des chevaux. Engourdis dans les voitures par leur long voyage, les poissonniers sommeillaient, enveloppées dans leurs lourdes houppelandes, tenant machinalement les guides. Les chevaux connaissaient leur chemin. Lorsque les premiers attelages arrivaient sous les pavillions de fer, il se produisait alors un embouteillage et le crissement des freins remontait en un grincement aigu jusqu’au faubourg Poissonnière. Les charretiers se réveillaient brusquement, s’invectivaient, se dressaient sur leur siège. Il fallait attendre que les premiers déchargent leurs marchandises. Les chevaux piaffaient, tapaient du pied. La plupart des hommes descendaient de voiture et allaient boire un petit verre de goutte dans les bistrots qui ouvraient leurs volets.

Ce vendredi-là, à l’arrière d’une des charrettes se tenait assise une petite fille. Ses jambes et ses pieds nus se balançaient et le garçon ne remarquait plus que cette peau blanche. Il s’approcha. La petite fille, la tété penchée, le visage caché par ses cheveux blonds embroussaillés qui lui retombaient sur les yeux, ne le voyait pas. Lui, de toute manière, ne regardait que ces jambes dodues, qui se balançaient. Lorsqu’il fut tout près, il entendit que la petite fille chantonnait une comptine. Il avança la main, toucha l’un des mollets.

— Bas les pattes ! A-t-on idée !

Alors il aperçu son visage, une figure chiffonnée, avec des yeux bleus. Il savait que la mer était bleue. La petite fille venait de la mer. Elle sentait d’ailleurs très fort le poisson, ou bien cela venait de la charrette. Pour en avoir le cœur net il mit le nez sur l’une des jambes blanches.

Elle se débattit.

— Veux-tu pas renifler comme ça. D’abord, d’où sors-tu ?

Il montra le bas de la rue, d’un air vague.

— On est arrivés, dit la petite fille. C’est pas trop tôt.

Elle sauta de la charrette. Le garçon était beaucoup plus grand qu’elle.

— Moi j’ai douze ans, dit-il, et toi ?

— Onze.

— Tu es bien petite.

— C’est toi qui es grand. Quel échalas ! On dirait un hareng saur.